Despite assurances to regulators and competitors that the auction wouldn’t really be pay-for-play, and wouldn’t omit the popular, purpose-driven search engines from rankings, the results have done nothing to increase competition in search. The latest ‘winners’ were mostly little known profit-hungry search engines like GMX, PrivacyWall, and info.com, who crowded out purpose-driven operators. Purpose-driven search engines like Ecosia (which I founded), DuckDuckGo, Qwant, and Lilo have next to no visibility on Android in this pay-to-play system, and the origin of some of the actual winners, is worthy of cross-examination. Info.com, for example, makes money in part by buying up search ads on Google and redirecting the searcher to another page of adverts on its own engine. Info.com will now pay money to Google (through the auction format) for the right to place these ads, which Google already makes money from. Quite literally, they are helping Google profit from a ruling that was meant to curb their dominance, not expand it.

Next to no Android phones have the choice-screen built in, because of COVID

Even if the auction results were more balanced, real choice is not getting through to consumers, since Google decided that the so-called choice-screen would only be built into new devices. As with almost every industry, the coronavirus has completely altered the economic landscape in smartphone manufacturing, with sales down as much as 50% during the height of the pandemic and supply chains disrupted or shut. Delays have hit production lines for smart devices and far fewer Android phones have been sold since the choice screen went live in April 2020. My team and I estimate a tiny proportion of users have actually been presented with the screen. Regulators need to realize that barely anyone can currently see this choice-screen and adapt their regulation accordingly.

No resolution to the 2018 EU ruling

Since the 2018 ruling against Google, market conditions for rivals are now significantly worse. Alternative search engines are struggling — Ecosia, for example, saw revenues cut in half at the height of the pandemic, and Cliqz, a privacy-centric search engine, collapsed in May — citing COVID and Google’s abuse of the market. We believe that the EU Commission was willing to give the auction process a chance because it wouldn’t necessarily discriminate based on price. But you only have to look at the results of this auction to see that the opposite is now the case. Google’s dominance of the search landscape still stands at 93%, and regulators must now consider what else can be done to ensure search rivals can more effectively challenge them.

Addressing false scarcity where there is none

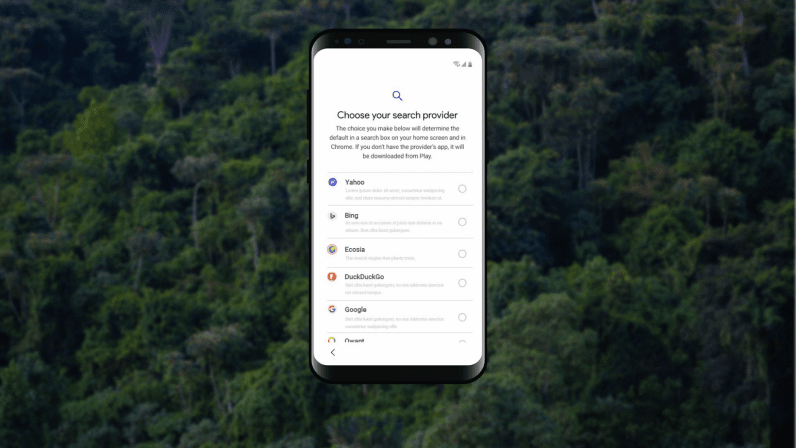

Limiting consumer choice to just three options has not only created this upward cycle of unnecessary cost for search providers, but it’s also a bad deal for Android users. Imagine walking into a supermarket where there are only three varieties of chocolate or coffee? The figure of three is unnecessarily arbitrary, and contrary to the spirit of the 2018 ruling. Android users deserve to be able to freely choose which search engine they use, and there is no technical or logistical reason why this is not possible. Regulators should pressure Google into opening up the choice-screen to all search engines, not just those willing to pay for the privilege, to ensure that all Android users have access to the choice relevant to them. As you can see from our mockup below, there’s no reason why this could not work.

A genuine fair-choice screen, free of financial influence

The most popular alternative search options are not profit-hungry Google affiliates. They are privacy-friendly, climate-friendly options that users turn to to support a specific cause, like fighting climate change. As such, the pay-for-play auction model does not work in our favor, as it makes it uneconomic for us to bid high, therefore excluding all the genuine rivals (and the ones that users willingly opt for), like Ecosia, DuckDuckGo, or Qwant. If we’re going to have a screen which is genuinely fair, it should not discriminate on price. Google must urgently look at a genuinely fair-choice screen that doesn’t limit access, or favor the largest competitors.

Act now, or lose competition all together

Since the 2018 ruling, Google has said it is taking measures to open up competition but its actions tell a different story. They’ve done everything they can to protect market share, and to stymie the growth of alternative rivals. Now some alternative search engines are teetering on the verge of going under and may struggle to survive the coming winter. We cannot wait several years before looking back to say, ‘well that didn’t work’. These issues need addressing now — while there still is a search engine market that isn’t just Google. What we’re calling for is fairly easy for Google to implement. They have spent the last 18 months building the technical infrastructure for a choice screen, so adding every player (as demonstrated in the model above), rather than just three, wouldn’t require much additional resource or investment from them. After all, this is how it works on Chrome, so what applies there should apply on Android. If the EU is not to look helpless in the face of Google, it must realize that the Android auction needs to be reworked so that a genuine choice can be offered to all of the EU’s consumers.